- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

Swedish Modern Design

A new exhibition looks at the fresh fabrics and furnishings that revolutionized interior decoration

Devoted to themes of national heritage, color, nature, and abstraction, the new installation Color and Comfort: Swedish Modern Design features a large cache of rarely seen midcentury furnishing fabrics from the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibition also includes works of furniture, glass, and ceramic designed by important Swedish industrial designers from the late 1920s to the early 1960s. Iconic pieces by the most prolific designer of that period, Josef Frank, are shown among rare examples from a multitude of other artisans, including Viola Gråsten, sisters Gocken and Lisbet Jobs, Stig Lindberg, Sven Markelius, and Elizabeth Ulrick.

With the goal to modernize the household furnishings industry after the First World War, designers across Europe sought to make traditional, handcrafted decoration accessible not only through innovations in industrial manufacturing practices—such as larger, wider looms and machine-capable printing—but also through design, with appealing patterns that were affordable to produce.

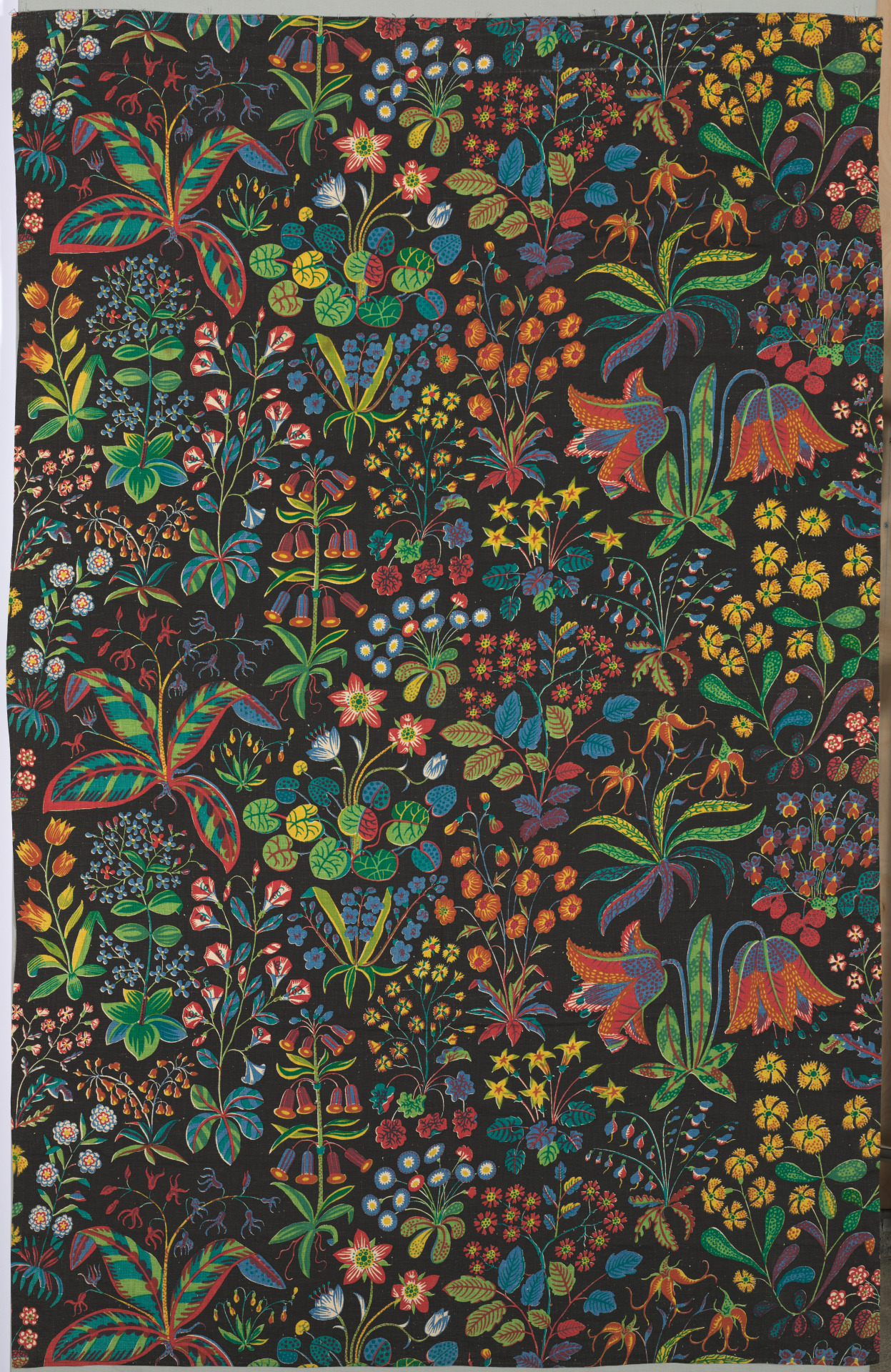

In Sweden the push toward simple, economical living attracted young artisans eager to revolutionize the home furnishings industry. In the early 1930s one such émigré was architect and designer Josef Frank, who left Austria as the persecution of Jews mounted. Typical of industrial designers of that era, Frank worked in several sectors of the furnishings industry, designing furniture and textiles for multiple companies. His influential work included brightly colored, naturalistic patterns based on botanical prints by 18th-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. Moved by the beauty and detail of these prints, Frank used them to decoupage the outside of cabinets and as inspiration for his own textile patterns. Examples of both can be seen in this installation, showing his proficiency in design application.

Frank found kindred spirits in Sweden, especially among young professional women working in the fields of interior decoration and home furnishings. His collaboration with Estrid Ericson, founder of Stockholm-based manufacturer Svenskt Tenn, exposed his work to a broad audience through exhibitions and installations in department stores worldwide, including Kaufmann’s in Pittsburgh. Soon his work became synonymous with the best of Swedish and Scandinavian design, attracting the attention of critics and curators alike. Frank’s particular mode of organic, sinewy, naturalistic patterns laden with bright, contrasting colors on creamy white or inky, dark backgrounds also influenced other designers eager to embrace this popular stylized motif.

After the Second World War, design in Sweden took two divergent paths: one sought to reclaim the historical heritage appropriated by National Socialism during the war through traditional patterns and decoration, and the other followed the strongly modernist trends in contemporary architecture. Evocative examples of both styles are found in the CMA’s collection and help articulate a particularly Swedish sensibility synonymous with trends throughout Scandinavia during the 1950s and ’60s.

The bright colors in contrasting patterns that Frank made famous before the war can be seen in the abstract designs he later favored. In these works, pure geometry becomes distorted in wavy, less rigid lines carefully synchronized with how these textiles would look as a curtain bunched at a window or upholstered on a couch.

The same palette and use of abstract patterning is evident in the examples of Swedish glass and ceramics on view in the installation. Innovations in glassblowing and machine finishing allowed manufacturers to produce works of high artistic quality at relatively affordable prices, in much the same way the textile industry had transformed the availability of well-designed fabrics. All of these works enhance our understanding of the role of Swedish interior furnishings in uplifting and brightening an otherwise spartan existence that prevailed during both the economic depression of the 1930s and the lean postwar decades.

These remarkable examples represent an even larger group of works gathered during the period by the CMA’s education department for its Extensions program, which brought art to schools and libraries throughout northeast Ohio for more than 75 years. More recently, the textiles have been the subject of study for a class of graduate students from the CMA-CWRU joint program in art history and museum studies. Their research informed the development of this exhibition and has led to a much better understanding of the context of these works and their designers.

Cleveland Art, January/February 2019